In Shankar’s 1996 film Indian, Crazy Mohan’s character threatened to expose corruption through a national newspaper, while the film’s lead character would later hijack a television station to send a sharp anti-corruption message. The same filmmaker then went on to film one of the most iconic on-screen television debates in Tamil cinema, in 1999’s Mudhalvan. Cut to 2014, we had Vijay holding a trend-setting press conference in the climax of A.R. Murugadoss’ Kaththi. And now, Shankar has returned with a sequel to Indian, in which a gang of keyboard warriors expose corruption through social media.

Enough and more has been said about the advent of social media in the last 10 years when platforms like Facebook, Twitter and Instagram saw a boom among the South Asian populace. Rightly called a man-made animal on the loose, these platforms have cast a long, deep shadow on our lives — they can now even make or break governments — and hence, have found their place on the silver screen.

Let’s look at how Tamil filmmakers have incorporated social media into their stories; from replacing news media as a medium to address the gallery, to using them as a tool to bridge plot points.

Using social media as just ‘media’

Using news media as a medium of whistleblowing has for long continued to be a favourite trope among Tamil filmmakers. Remember how Taapsee Pannu’s reporter character exposed the bulletproof vests scam in Arrambam? The power of the fourth wall of democracy has often been used to show a consolidation of public opinion, which builds pressure on authorities, like in Atlee and Vijay’s Theri. Many films of actor-turned-politician Vijay, like Thamizhan, Kaththi, and Mersal have used press conferences to tell audiences a message without breaking the fourth wall; this is a trope that can be looked at as an evolution from the Parasakthi-like or Citizen-like speech by the hero at a courthouse.

Now, where does social media feature here? Since the late 2010s, the sensational exposé in the pre-climax features social media as a part of ‘media,’ a homogenised mixture of all mediums where news can be consumed. In the 2018 film Sarkar, Vijay talks directly to the camera, without breaking the fourth wall, as he’s shown talking via Facebook Live with live reactions appearing on the screen. Films like Raame Aandalum Raavane Aandalum show montages of people looking at the sensational turn of events on their TV screens, or on YouTube and Facebook.

A still from ‘Sarkar’

| Photo Credit:

Sun NXT

Social media, as a tool in storytelling

Notably, the younger crop of directors, who grew up witnessing the social media boom up close, have found fresher ways to incorporate these mediums as a tool in their storytelling. These platforms naturally featured in films that warned you of the dark, uglier sides of this technology. The protagonist in Lens falls in a trap set by the antagonist via a fake Facebook account. P.S. Mithran’s Irumbu Thirai warned of the consequences of extensively sharing personal information on social media, while Aadai disparaged the toxic social media-driven prank culture by showing the depths to which a YouTube channel sinks to make content.

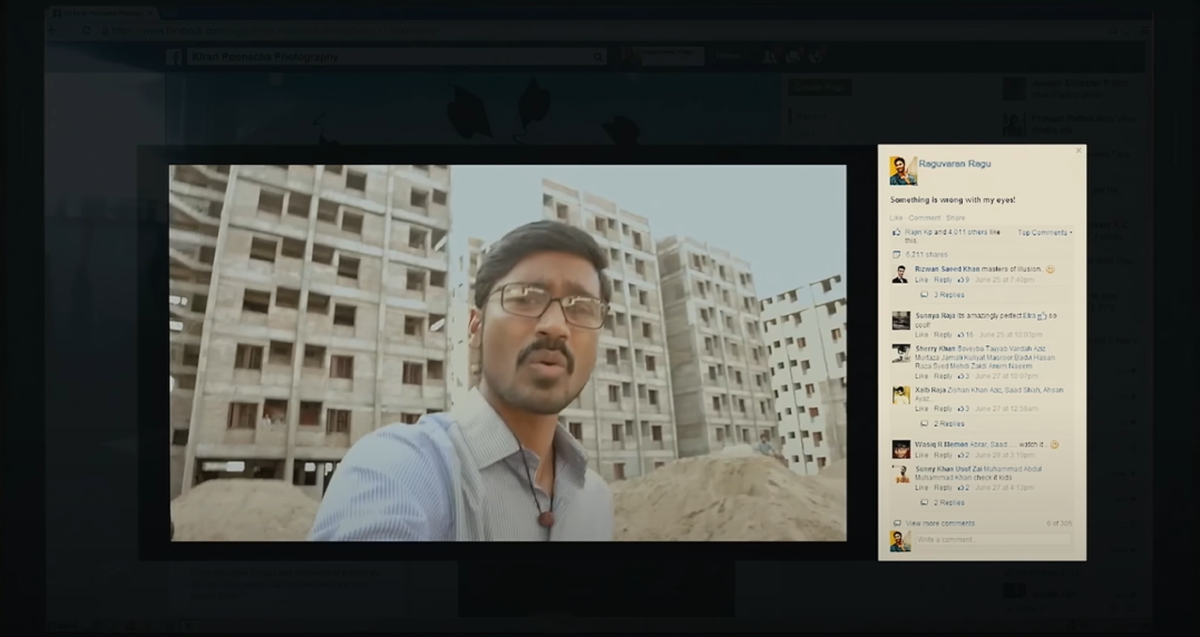

Interestingly, Dhanush’s 2014 film, Velai Illa Pattadhaari, was one of the first big-star films to tap into the power of social media in an efficient way; the film showed how the Groups feature of Facebook can be used to mobilise like-minded people or to unionise them.

A still from ‘Velai Illa Pattadhaari’

| Photo Credit:

Sun NXT

Writers have used social networking sites to bridge plot points as well, like how an elderly man finds his long-lost love through Facebook in Dhanush’s directorial debut, Pa Paandi. In Nithilan Swaminathan’s debut film, Kurangu Bommai, a man’s Facebook post on finding a lost bag leads to an uneventful turn. In Aruvi, an HIV patient sends a plea of love to her friends through a video message on Facebook. There have also been a few romance films like Love Today that have commendably adapted how young generation relationships are thriving through these platforms.

As a quick-fix to help with writing

However, top-hat filmmakers are still catching up on the social and cultural impact of such technological advancement. Yes, in some stories, like Raame Aandalum Raavane Aandalum or Ka Pae Ranasingam, whistleblowing through news and social media might be the only option to help the overpowered protagonists. But you do feel a certain fatigue with how most films use this as an excuse for inadequate writing, sometimes as a means to a quick resolution. It’s also worn-out and shallow to say that merely exposing an issue on social media is enough to bring about a real-life change.

In Indian 2, for instance, Shankar’s usage of hashtag trends is just lazy; this is a film in which a hashtag with a million tweets is conclusively told as the voice of a nation!

A private YouTube channel that jumps to conclusions without proper investigation is labelled good citizen reporting. A 106-year-old vigilante, active on social sites, decides to come out of retirement, not when millions of crimes were spoken about in all these decades, but only when his identity is plastered as a hashtag, #ComeBackIndian. Apart from Senapathy’s vigilante justice and his solution to corruption which sparks a wildfire online, the film misses out on at least a briefing on a pragmatic, real-world solution.

Given how Tamil films have used these platforms majorly to drive forward social themes, it’s pivotal to understand that online movements have transient results. Social media can consolidate and project viewpoints — like a common man’s solution to corruption — but mere projections cannot cause any perceivable impact until they result in a change in laws, public opinion, or the larger system.

Why the medium remains underutilised in Tamil cinema

Even Goundamani’s comedy couldn’t stay away from including social media — as was evident in 2016’s Enakku Veru Engum Kilaigal Kidayathu — but Tamil cinema still hasn’t come to terms with using social media as a narrative tool, except for these aforementioned usages and exceptions. Even realistic slice-of-life depictions have opted for characters who seem oblivious to how social media affects their lives — which makes you wonder if these films themselves are a way for a storyteller to cope with the effects of social media, by building a world devoid of it.

For such reasons and more, these innovations remain only superficially used in our films. In Hindi cinema too, we have seen titles that use media attention, or an expose on social media, in the final showdown.

Much recently, Atlee continued his trope of using media as an anti-establishment tool with Jawan. However, there have also been titles like Kho Gaye Hum Kahan and Love Sex Aur Dhokha 2 in Hindi, or Searching, Missing, Ingrid Goes West,Not Okay and Mainstream in English, that have shed light on relevant topics such as influencer culture, cancel culture, and the new-age phenomenon that is ‘stardom through social media.’

Maybe there is a hesitancy to watch a movie that entirely takes place on a computer screen, and so, Tamil cinema has yet to make ‘screen-life’ films like Malayalam’s C U Soon or the English titles Searching, Host and Unfriended: Dark Web.

A still from ‘C U Soon’

| Photo Credit:

Prime Video

Except for a series like Fingertip, there haven’t been attempts in mainstream Tamil films to dig deeper into the psychological ramifications of growing up in the social media era, where online personas and their following directly determine someone’s self-esteem.

In conclusion, while it’s commendable how everyday technology has seen such an evolution on screen, it’s time to look at it as not just a means to end a story, but embrace it for what it actually is.